The Road to Academic Success and Social, Emotional, and Mental Wellness

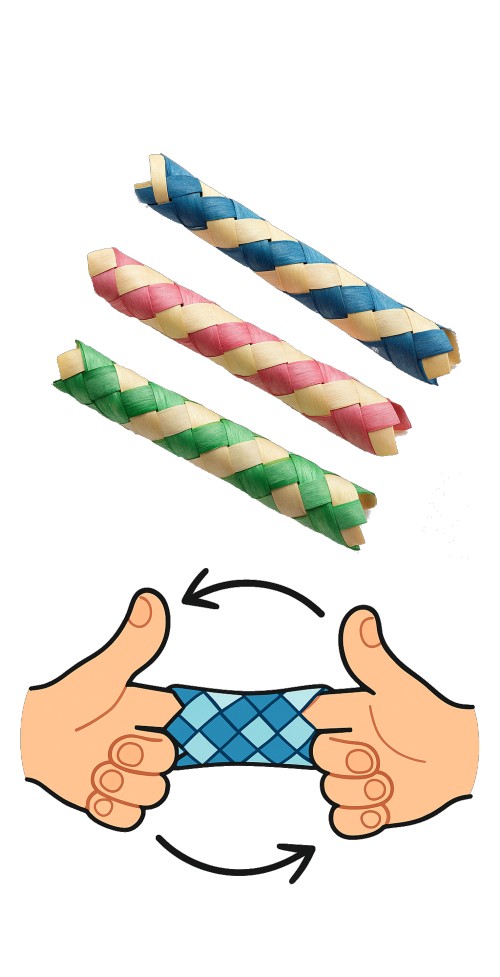

Well, that subtitle sums up many of the goals of schools these days. Who knew you could accomplish it all through play? The reality is that the more schools are concerned about academic achievement, the more they double down on lessons – probably the least effective path to student achievement. It’s like those bamboo finger cuffs I used to play with as a child. You put your two index fingers into the ends and then try to pull them out. The more you pull them out, the more the cuff tightens around your fingers, making it nearly impossible to free them. But if you think counterintuitively and push both fingers toward each other, the cuff loosens and you can wiggle out and escape!

Apply that to the vicious cycle in which schools are caught. The more students fail to learn, the more lessons we teach them, the more time we teach ELA and math, the more computer drills we give them. I’ve been in the teaching profession for over 40 years: That approach doesn’t work. But if you stepped back, loosened the grip, and let students “be” – let them play, create, imagine, explore, question, pursue – you’d find they actually learn a lot and build the foundational skills for learning: executive function. Armed with executive function, they can learn anything!

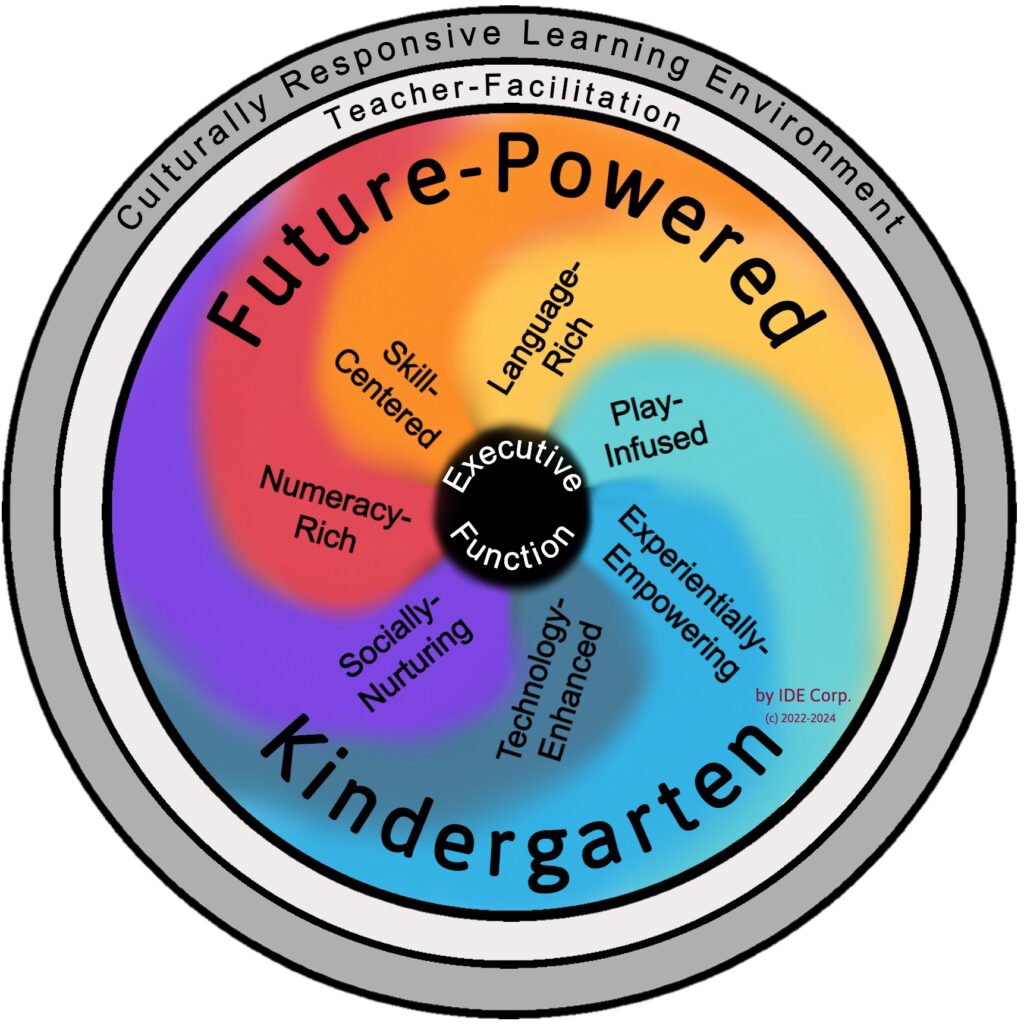

Get Kindergarten Right!

If kindergarten is where we lay the foundation for lifelong learning, then play isn’t a break from the work – it is the work. Play isn’t busy work while the teacher attends to other students; it’s critical to building the skills to learn, social skills, and a strong sense of self. I recommend including at least a half-hour a day (beyond recess) for free play, and then including at least an hour more of choice-driven, play-based academic activities (letter puzzles, number games, letter tiles, Unifix cubes, animal and habitat cards, etc.). While the latter represent hands-on, fun, engagement with academic concepts and skills, and are hugely important in kindergarten, they are not the same as play.

Seen and Heard During Kindergarten Play

- – A student is in the play kitchen cooking food while on a cell phone having an imaginary conversation with a friend.

- – Two students use building blocks and ramps to create courses for their race cars.

- – One student is dressed as a doctor having a conversation with another dressed as a firefighter.

- – A student is creating a zoo with animal dolls.

- – Two students (one speaks only English, the other only Spanish) are playing together in the kitchen. One picks up a strawberry and says “strawberry;” the other says “fresa,’ and the first repeats “fresa.”

- – A student uses kinetic sand to sculpt an image of himself.

None of these experiences was scripted; none was assigned, perhaps other than the center to use. Students simply invented what they wanted to do in the center.

Play Is More Important Now Than Ever

When I was a child, my friends and I would go out and play after school. We had to amuse ourselves. We’d jump on our bicycles and make up all sorts of scenarios; we’d build forts; we’d collect materials and create pieces of art; and on and on. We knew when the streetlamps came on, we had to go home. Sadly, the world is not as safe for children to roam free these days. So we fill their lives with scripted experiences. After school is basketball practice, then dance; another day it’s swimming lessons; and so on. While all of these experiences are powerful and build many skills, they do not take the place of imaginative, creative play.

Facilitated Play: The Play That Goes to School

In the Future-Powered Kindergarten, teachers use play as a way to build executive function skills. Therefore, it’s important for play to be facilitated. While students are playing, the teacher launches into action, first as an observer, then as a facilitator. Let’s look at just six executive function skills in terms of observation and then facilitation:

| Skill | Observe | Facilitate |

| Attending to a person or activity | – Does the student stay engaged in the activity without wandering away? – Does the student track a peer’s actions or listen when another is speaking? – Does the student respond appropriately when addressed during play? | – What are you working on? – What is your friend doing right now? – Can you tell me about what you’re building? |

| Holding onto information while considering other information | – Does the student pause play to retrieve needed materials and return to task? – Does the student continue an idea or storyline after an interruption? – Does the student manage multiple steps in pretend play (e.g., gathers food, cooks, serves)? | – What do you still need to finish that? – What were you just doing before you found that piece? – Can you show me what happens next in your story? |

| Identifying same and different | – Does the student match or sort objects during play (e.g., food by type or blocks by size)? – Does the student compare features of items or roles in dramatic play? – Does the student notice differences in others’ play and respond appropriately? | – How are those two things the same? – What makes this one different from the others? – Can you sort them another way? |

| Categorizing information | – Does the student group objects by size, color, function, or type? – Does the student assign roles or jobs during dramatic play (e.g., cook, customer)? – Does the student clean up by sorting items appropriately? | – Why did you put those together? – Is there another way you could group these? – What category do these belong in? |

| Working toward a goal | – Does the student plan or persist in building or creating something? – Does the student express intentions (e.g., “I’m making a restaurant.”)? – Does the student revise or rebuild if things don’t work as planned? | – What are you trying to make? – What’s your plan if it doesn’t stay up? – What will you do next? |

| Maintaining social appropriateness | – Does the student take turns and share space or materials respectfully? – Does the student use appropriate language and tone during play? – Does the student respond empathetically or adapt when conflict arises? | – How do you think they felt when that happened? – What could you say to invite them in? – Is there another way you can solve that problem together? |

What the Research Says

New York State’s guidance on play (2024) reminds us that play is a vehicle for developing 21st century skills: communication, creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. These are directly linked to the executive function skills that predict success not just in school, but in life.

“Play is fundamentally important for learning 21st century skills . . . which require the executive functioning skills that are critical for adult success.”

Facilitated play is not frivolous. It is not off-task. It is not downtime. When done well, it is one of the most powerful instructional strategies we have.

Building Play Into the Day

In the Future-Powered Kindergarten, we don’t schedule 40-, 60-, or 90-minute blocks of one subject. The kindergarten day is a mosaic of short, engaging learning bursts – 20 minutes of math, a movement break, 20 minutes of phonics, facilitated play, reading time, creative centers. This pacing works with young learners’ cognitive rhythms, not against them. And play is woven throughout – not as an isolated block, but as a central approach. Consider that:

1. Sustained Attention Has Natural Limits

- – Young children typically can focus actively for about 2–5 minutes per year of age (e.g., 10–20 minutes for kindergartners).

- – Long instructional blocks often exceed their cognitive stamina, leading to mental fatigue and diminished returns.

2. Frequent Transitions Support Executive Function

- – Switching tasks strengthens cognitive flexibility (executive function ).

- – Moving between structured academic work and unstructured or semi-structured play supports task initiation, impulse control, and shifting attention.

3. Movement and Play Boost Brain Function

- – Short movement breaks increase oxygen flow to the brain, improving alertness and performance.

- – Facilitated play builds working memory, emotional regulation, and problem-solving skills.

4. Distributed Practice = Better Retention

- – Spacing out learning (like two 20-minute math sessions separated by other topics or activities rather than one 40-minute block) supports long-term retention and skill transfer.

- – This approach aligns with the spacing effect, which shows people learn more effectively when content is reviewed over time.

5. Autonomy and Motivation

- – Inserting choice time and free play respects students’ need for agency and self-regulation, increasing motivation and engagement.

- – It can reduce power struggles and behavior issues, especially in younger children.

So use play to create a daily schedule that weaves academic lessons with more student-driven opportunities to explore, create, reflect, relax, and recharge.

Play with a Purpose

The best learning doesn’t feel like learning at all. It feels like exploration. It feels like joy. It feels like play.

Facilitated play is how we help young learners:

- Build resilience when their first design falls over.

- Practice communication when a peer has a different idea.

- Demonstrate metacognition when they’re asked how their character might solve a new problem.

And most importantly – it’s how we ensure students are learning how to learn.

For more on IDE Corp.’s Future-Powered Kindergarten, see a “Look Into” and a table of what it “Looks Like” or contact us at solutions@idecorp.com