While there is certainly a place in your learning environment for whole-group instruction, a large part of a student’s day needs to involve engaging in tackling instructional activities. For the greatest results, start with thinking through how we learn and selecting activities to support that.

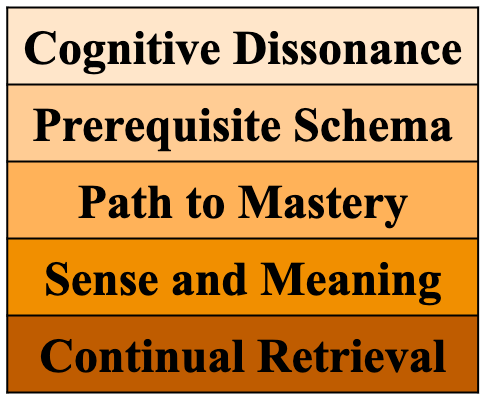

Consider the learning progression (from the brain’s-eye view):

- Cognitive Dissonance — Wait, something does not make sense here! There’s something I don’t know! I don’t like that. I must fix this!

- Prerequisite Schema — What do I already know? Surely that can help me understand this. I’ll make connections!

- Path to Mastery — I see light at the end of the tunnel! There are opportunities for me to learn in ways that work for me!

- Sense and Meaning — I get it! This fits into what I know; I see how this fits into my world; I see how I can use it!

- Continual Retrieval — Oooh, look! I need that stored information! Wait! I need it again over here. Again, I need that information! It must be awfully important. I better store it away for good!

Ah, to see learning through the eyes of the brain! But you get the point. So now translate that into activities in which students will engage in order to learn.

In a learning environment, you’re creating a “landscape of opportunities for academically rigorous learning” that support that progression. Students should be able to access and benefit from these as easily at home as in school. They should not be “losing out” if they are not in school; that may mean more short, recorded videos by the teacher to be made available to students; it also means other forms of learning through text, interactive websites, and more.

There are five types of activities that should be included as you create your classroom’s landscape of learning opportunities:

Learning Activities — These are activities that are meant to teach through step-by-step directions or explanation. They should be linked to a greater goal for learning (see “Anchoring the Learning”). They should take into account prerequisite schema, and, actually, a student shouldn’t even be engaging in a learning activity if they lack the prerequisite schema. They should attend to that first. Learning activities should be very focused on narrow content and not include any extraneous information that would confuse the brain (such as sarcasm, jokes, and entertainment to engage students; learning engages students). Independent learning activities should offer students some feedback: through self-checking their answers, seeing a sample of the final product, or other descriptions against which they can match their work. Learning activities should resonate with students’ preferred learning styles, though you should always challenge students to try activities outside of their comfort zone in addition to those they prefer. Start, at least, with a screencast or video version and a text-based how-to sheet. Then add learning centers, interactive websites, audio recordings, and more. A live small-group mini-lesson fits into this category as well. For more, see my video on “Learning vs. Practice Activities.“

Practice Activities — These are meant to allow students to put what they learned to the test! Repetition of skills is important to build fluency. In practice activities, students have to do the work! Thus, you would not typically use a screencast for student practice, as students are not the ones doing the work. Instead, students should be writing, creating, calculating, sketching, and more. They should show you what they know, but return to a learning activity when they are confused and need help.

Application Activities — After learning and practice, it’s time to use this new learning. Have students use it to solve a different problem from the ones used in learning and practice. Have students apply the learning to a real-world situation.

Assessment Activities — Self-assessment is powerful. Let students complete an assessment and check their answers to determine how well they learned the skill or concept. Let students track if they are just getting started, practicing, or have achieved mastery (see the Learning Dashboard as a tool for students to monitor their progress based on assessment activities).

Reflection Activities — Encourage students to pause and reflect on what they’ve learned, how they will use it, and what more they want to learn. One tool is a Digital Efficacy Notebook, but any form of reflection on their learning will do. Ask students to reflect not only on what they learned, but also how hard or easy it was. Allow for metacognitive reflection — thinking about their own thinking and learning process — in addition to the content.

Designing a learning environment requires being deliberate about the teaching-learning relationship. Then again, this level of purposeful instructional design would serve students well even if school were only going to take place in a brick-and-mortar world. 🙂

For More:

Join a Virtual Learning Community on Designing Learning Environments: www.edquiddity.com/VLC